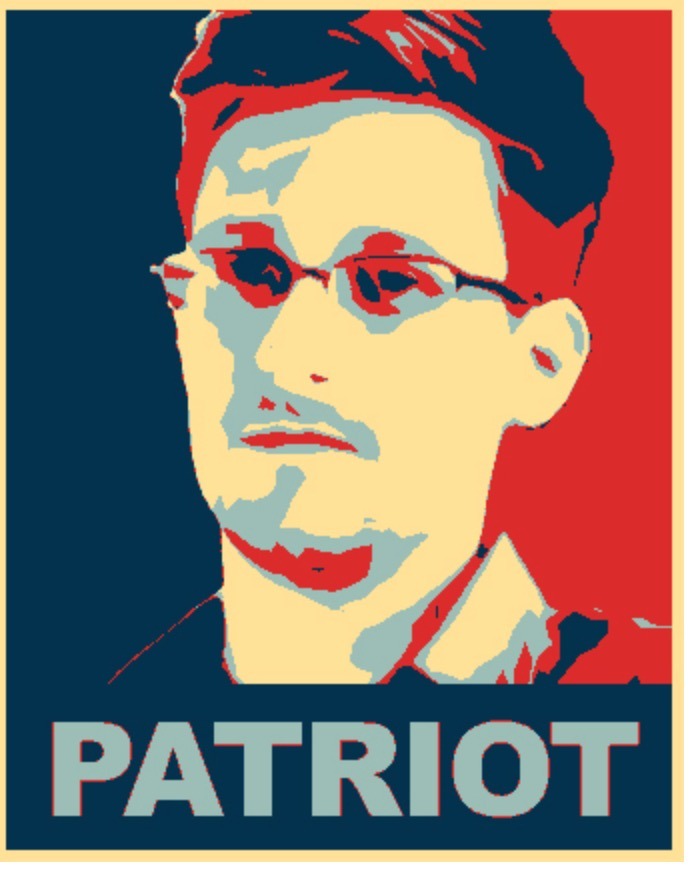

A Whistleblower Manifesto by Edward Snowden

I’ve been waiting 40 years for someone like you.” Those were the first words Daniel Ellsberg spoke to me when we met last year. Dan and I felt an immediate kinship; we both knew what it meant to risk so much — and to be irrevocably changed — by revealing secret truths.One of the challenges of being a whistleblower is living with the knowledge that people continue to sit, just as you did, at those desks, in that unit, throughout the agency, who see what you saw and comply in silence, without resistance or complaint. They learn to live not just with untruths but with unnecessary untruths, dangerous untruths, corrosive untruths. It is a double tragedy: What begins as a survival strategy ends with the compromise of the human being it sought to preserve and the diminishing of the democracy meant to justify the sacrifice.A single act of whistleblowing doesn’t change the reality that there are significant portions of the government that operate below the waterline, beneath the visibility of the public. Those secret activities will continue, despite reforms. But those who perform these actions now have to live with the fear that if they engage in activities contrary to the spirit of society — if even a single citizen is catalyzed to halt the machinery of that injustice — they might still be held to account. The thread by which good governance hangs is this equality before the law, for the only fear of the man who turns the gears is that he may find himself upon them.Hope lies beyond, when we move from extraordinary acts of revelation to a collective culture of accountability within the intelligence community. Here we will have taken a meaningful step toward solving a problem that has existed for as long as our government.Not all leaks are alike, nor are their makers. Gen. David Petraeus, for instance, provided his illicit lover and favorable biographer information so secret it defied classification, including the names of covert operatives and the president’s private thoughts on matters of strategic concern. Petraeus was not charged with a felony, as the Justice Department had initially recommended, but was instead permitted to plead guilty to a misdemeanor. Had an enlisted soldier of modest rank pulled out a stack of highly classified notebooks and handed them to his girlfriend to secure so much as a smile, he’d be looking at many decades in prison, not a pile of character references from a Who’s Who of the Deep State.

This dynamic can be seen quite clearly in the al Qaeda “conference call of doom” story, in which intelligence officials, likely seeking to inflate the threat of terrorism and deflect criticism of mass surveillance, revealed to a neoconservative website extraordinarily detailed accounts of specific communications they had intercepted, including locations of the participating parties and the precise contents of the discussions. If the officials’ claims were to be believed, they irrevocably burned an extraordinary means of learning the precise plans and intentions of terrorist leadership for the sake of a short-lived political advantage in a news cycle. Not a single person seems to have been so much as disciplined as a result of the story that cost us the ability to listen to the alleged al Qaeda hotline.If harmfulness and authorization make no difference, what explains the distinction between the permissible and the impermissible disclosure?The answer is control. A leak is acceptable if it’s not seen as a threat, as a challenge to the prerogatives of the institution. But if all of the disparate components of the institution — not just its head but its hands and feet, every part of its body — must be assumed to have the same power to discuss matters of concern, that is an existential threat to the modern political monopoly of information control, particularly if we’re talking about disclosures of serious wrongdoing, fraudulent activity, unlawful activities. If you can’t guarantee that you alone can exploit the flow of controlled information, then the aggregation of all the world’s unmentionables — including your own — begins to look more like a liability than an asset.At the other end of the spectrum is Manning, a junior enlisted soldier, who was much nearer to the bottom of the hierarchy. I was midway in the professional career path. I sat down at the table with the chief information officer of the CIA, and I was briefing him and his chief technology officer when they were publicly making statements like “We try to collect everything and hang on to it forever,” and everybody still thought that was a cute business slogan. Meanwhile I was designing the systems they would use to do precisely that. I wasn’t briefing the policy side, the secretary of defense, but I was briefing the operations side, the National Security Agency’s director of technology. Official wrongdoing can catalyze all levels of insiders to reveal information, even at great risk to themselves, so long as they can be convinced that it is necessary to do so.Reaching those individuals, helping them realize that their first allegiance as a public servant is to the public rather than to the government, is the challenge. That’s a significant shift in cultural thinking for a government worker today.At the heart of this evolution is that whistleblowing is a radicalizing event — and by “radical” I don’t mean “extreme”; I mean it in the traditional sense of radix, the root of the issue. At some point you recognize that you can’t just move a few letters around on a page and hope for the best. You can’t simply report this problem to your supervisor, as I tried to do, because inevitably supervisors get nervous. They think about the structural risk to their career. They’re concerned about rocking the boat and “getting a reputation.” The incentives aren’t there to produce meaningful reform. Fundamentally, in an open society, change has to flow from the bottom to the top.And when you’re confronted with evidence — not in an edge case, not in a peculiarity, but as a core consequence of the program — that the government is subverting the Constitution and violating the ideals you so fervently believe in, you have to make a decision. When you see that the program or policy is inconsistent with the oaths and obligations that you’ve sworn to your society and yourself, then that oath and that obligation cannot be reconciled with the program. To which do you owe a greater loyalty?As a result we have arrived at this unmatched capability, unrestrained by policy. We have become reliant upon what was intended to be the limitation of last resort: the courts. Judges, realizing that their decisions are suddenly charged with much greater political importance and impact than was originally intended, have gone to great lengths in the post-9/11 period to avoid reviewing the laws or the operations of the executive in the national security context and setting restrictive precedents that, even if entirely proper, would impose limits on government for decades or more. That means the most powerful institution that humanity has ever witnessed has also become the least restrained. Yet that same institution was never designed to operate in such a manner, having instead been explicitly founded on the principle of checks and balances. Our founding impulse was to say, “Though we are mighty, we are voluntarily restrained.”

When you first go on duty at CIA headquarters, you raise your hand and swear an oath — not to government, not to the agency, not to secrecy. You swear an oath to the Constitution. So there’s this friction, this emerging contest between the obligations and values that the government asks you to uphold, and the actual activities that you’re asked to participate in.By preying on the modern necessity to stay connected, governments can reduce our dignity to something like that of tagged animals, the primary difference being that we paid for the tags and they’re in our pockets. It sounds like fantasist paranoia, but on the technical level it’s so trivial to implement that I cannot imagine a future in which it won’t be attempted. It will be limited to the war zones at first, in accordance with our customs, but surveillance technology has a tendency to follow us home.Unrestrained power may be many things, but it’s not American. It is in this sense that the act of whistleblowing increasingly has become an act of political resistance. The whistleblower raises the alarm and lifts the lamp, inheriting the legacy of a line of Americans that begins with Paul Revere.The individuals who make these disclosures feel so strongly about what they have seen that they’re willing to risk their lives and their freedom. They know that we, the people, are ultimately the strongest and most reliable check on the power of government. The insiders at the highest levels of government have extraordinary capability, extraordinary resources, tremendous access to influence, and a monopoly on violence, but in the final calculus there is but one figure that matters: the individual citizen.And there are more of us than there are of them.

Michael Krieger

0 comments:

Post a Comment